THE KOHIMA JESUITS

50 Years of Educating NE India's Rural Poor

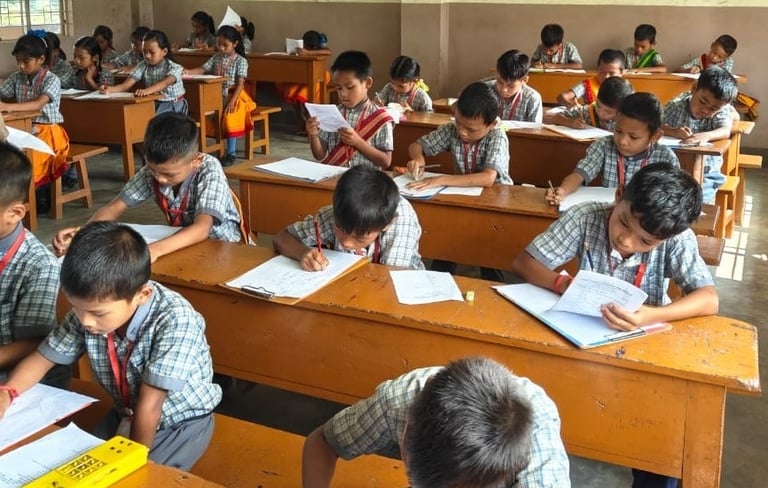

Looking back now, the story of the Jesuit schools in Northeast India has truly been one of unsolicited hope. Things happened unexpectedly; certainly not as the village folks had anticipated it. Nor, for that matter, not even the Jesuits. But since their arrival, some fifty years ago, the lives of numerous people in remote tribal villages of the region have been transformed, and often beyond measure.

But things did not pan out as planned. Various covert forces contravened to ensure the Jesuits would not find land for their school in Kohima. Instead, they found themselves pushed 15 kms to the south, to a tribal village called Jakhama. The village was neglected and undeveloped and, like most other villages of the region, the people of Jakhama were mainly subsistence farmers. They cultivated rice in terraced fields, as their ancestors had done before them, not aspiring for much more from life. The education offered in the local schools was such that those who could afford it sent their children to schools elsewhere. What soon became clear was the gulf between what the Jesuits imagined they would be doing and where they found themselves.

Disappointed, possibly, but not willing to back away, the Jesuits decided to start a school for the local children of Jakhama village. In that first year the students who enrolled were a motely bunch, with many who were bigger and older than their teachers. Notwithstanding many setbacks, the school thrived through the efforts of the early Jesuits and the Sisters who collaborated with them. Leaders from the neighboring villages were soon requesting the Jesuits for similar schools in their villages. Transportation facilities in those early years were poor and commuting daily from their villages to Jakhama was not a viable option.

While these schools were taking root in and around Jakhama village, two other Jesuits moved north, toward Tuensang and Kiphre, to set up a network of schools in villages and small towns located along an arterial road that connects the eastern part of the state. These schools, not unlike the ones around Jakhama, served populations that had never imagined their children could ever have access to a decent education. In fact, many did not have an idea of what good all-round education might look like.

Hope, as I understand it, not just about trusting that the things which are deeply desired will someday be realized. It is also about getting what one realistically never anticipated.

Spread across five of the seven states of northeast India today, the thirty-one Jesuit schools of the Kohima Region continue to serve the rural poor. But it has not always been easy for the Jesuits to focus their educational efforts almost exclusively on rural schools. Without any income-generating schools to support their plans for future expansion, or to subsidize their financially deficit village schools, the Jesuits have had to constantly depend on outside sources for funding. The pressure, and the temptation, to have a few urban schools has been strong. But the Jesuits have successfully held their ground, trusting that with God’s help they would find the necessary resources. And they have. So a mission impulse that began as a consequence of unanticipated circumstances continues now, after prayerful discernment, to be embraced intentionally as the preferred option.

Make no mistake – educating the rural poor was not the reason why the Jesuits came to Northeast India. In 1970, they were invited by the Government of Nagaland to establish a school in Kohima, the state capital, patterned on the lines of Northpoint. For those unfamiliar with Northpoint, it is a Jesuit residential school in Darjeeling that serves an affluent clientele. It is exclusive, elite and expensive. So the initial plan was really quite straight forward: the Jesuits would educate the children of small, but growing, clusters of affluent and ambitious Naga families.

Paul Coelho is a Kohima Jesuit. He holds a PhD from Marquette University in the USA and has been actively engaged in secondary and tertiary education in India and the USA. He currently serves as the Development Director for the Kohima Region.

This story first appeared in "Conversations in Higher Education" 2021

In 1985, the Jesuits established their first college. With many students leaving in search for colleges elsewhere, they felt the need to offer tertiary educational opportunities within the region. They established the college in Jakhama, the same village where they had accidentally landed some fifteen years earlier. By this time, however, there many who felt that the Jesuits should be in the urban hubs, establishing the kinds of educational institutions that they are reputed for. But the rural thrust did not change. Gradually, a second, and then a third, school came up in the surrounding villages. In ten years, the Jesuits had schools in almost every village in the region. They wanted to ensure that every child had access to a decent education if they so desired. By now, serving the rural poor had become the preferred option of the Jesuits, even shunning opportunities to be in the urban centres when they opened up.

It is important to recognize how these rural Jesuit institutions have inspired hope in their tribal students and their families. Let me quote Apong, a middle-aged resident of small village in Arunachal Pradesh, who I imagine echoed the sentiment of many other parents. He put it succinctly, saying, “We know you all [the Jesuits] could have gone anywhere. But we are so grateful you chose to come to us. If not for you, I would probably have been dead by now. I am not sure what may have become of my children. I imagine they would have continued living like me and our ancestors, in abject poverty, drunkenness and ignorance.” Living in a decent brick home now, which has replaced the bamboo structure which once was his home, Apong’s eldest son, Sanjay, is a youth leader and presently the secretary to the locally elected-member of the State Legislature. Jesuit alumni from other small tribal villages too, like Sanjay, are doctors and professors, bureaucrats and politicians, engineers and teachers, and researchers, and in a host of other professions that neither they nor their families could ever have imagined and which they almost certainly never anticipated.

Hope, as I was mentioning earlier, is not about the realization of what one desires. It is also about getting what one could never realistically expect. And hope is one thing that the Jesuit schools of the Kohima Region have given the rural poor of northeast India.

Then, in 1977, the Jesuits started a teachers’ training college in an adjoining village. They wanted to ensure the growing number of village schools could be staffed by trained local teachers. They also setup an agro-industrial institute in another village. Agricultural and vocational training were a part of the Jesuit educational plan for the region but, and rather unfortunately, this did not resonate well with local parents who desired an education that would prepare their children for government jobs if not a professional career.

Our Partners